I looked up the opposition of Saturn this year, and it turns out I was a bit late, because it was on August 27, 2023. A couple weeks have passed since Saturn was closest to the Earth, but it should still make for great viewing. It was a warm, clear night at home, so I set up my telescope for the first time in a year. I am sharing sketches of what I observed, to give you a sense of the view in the eyepiece.

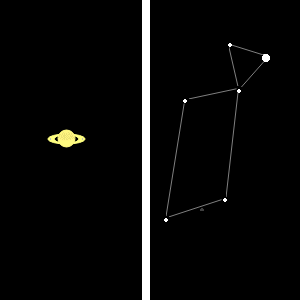

Saturn

It was 9:30 pm. Stellarium (astronomy app) told me that Saturn would cross the meridian at around 12:30 am. The meridian is the imaginary arc that connects the north and south poles with the zenith directly above us. Objects are highest in the sky when they cross the meridian, which enables us to look through the least amount of atmosphere. I wasn’t going to stay up late, so current conditions would have to do.

Stellarium indicated that Saturn would be southeast, and I was able to spot it easily. Saturn looks like a bright star, but it will not twinkle like a real star would. The best viewing spot was from my driveway, looking over my house. I was a little concerned that heat rising from my roof would create a shimmering mirage.

The finderscope on my refractor telescope centered on the planet easily. I inserted my 15mm plossl eyepiece, which gives 60x magnification. Saturn’s characteristic ringed shape was unmistakable. The image looked nice and steady, so I added a 2x barlow lens to double the magnification. At 120x, my 100mm (3.9″) refractor gives bright views with good contrast and color. Here is a digital rendering of what I saw:

I could easily make out two moons, the brightest being Titan. The disk of the planet was bright yellow, with darkening in the northern hemisphere. The Cassini division (gap between the rings) was hinted at in the ansae (protrusion of the rings). I just read that up to 6 moons can be seen through a telescope, but I only recall seeing two.

Using my 10mm plossl with 2x barlow, I boosted magnification to 180x. The seeing (atmospheric stability) was good enough to support this, with momentary shimmering between steady views. It is a dimmer image, and I did not see additional detail. I prefer the view at 120x.

M57 – the Ring Nebula

Directly above Saturn was a bright star, Altair. In the summer, a bright asterism (collection of stars that is not a constellation), called the summer triangle dominates the sky. It is an isosceles triangle formed by the bright stars Altair, Deneb, and Vega. Altair is in the constellation Aquila (the eagle), Deneb is in Cygnus (the swan), and Vega is in Lyra (the lyre). On a clear summer night, go out and try to find the summer triangle.

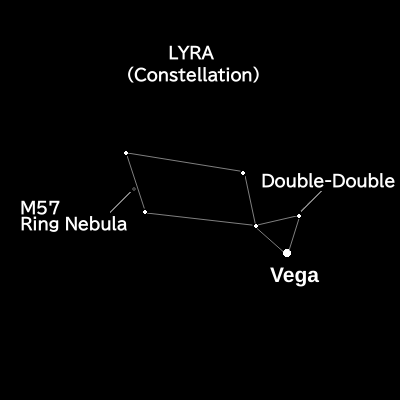

Upon seeing the summer triangle, I felt the urge to visit an old friend, the ring nebula, which is an astronomy icon. You might recognize it after doing an image search for it. The ring nebula is a planetary nebula, formed by the ejection of ionized gasses from a star at the end of its life cycle. It is also referred to by its number in the Messier catalog, M57. Located in the constellation Lyra, M57 is relatively easy to find.

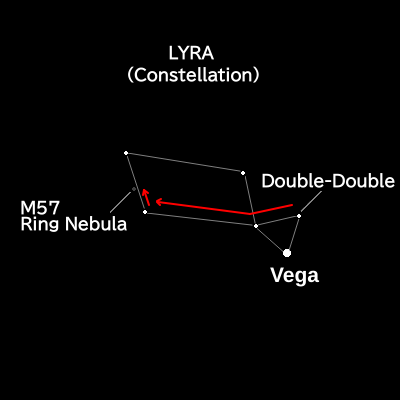

The best way to locate Lyra is to first find Vega, the brightest star in the summer sky, and part of the aforementioned summer triangle. Confirm it is Vega by the nearby stars that form a parallelogram. The ring nebula is located on the side of the parallelogram that is furthest from Vega.

In my finder scope, I can spot the Double-Double, a pair of double stars that are actually 4 stars under higher magnification. From there, I move in a slightly crooked line to the bottom of the parallelogram. In my 9x finder scope, M57 is visible as a small gray blob that is less bright than surrounding stars. It is slightly off-center between the stars that form one side of the parallelogram. You can try to use averted vision (looking slightly to the side) to better see this object.

The ring nebula is an object that is interesting to observe at any magnification. I started at 60x with my 15mm eyepiece; its oval shape and ring structure were recognizable. Pushing to 120x with my barlow, the nebula becomes dim, and averted vision is recommended to see more structure in the ring. I do not see much, if any, color. However, I can see the central star and some nebulosity (ionized glow) inside the ring. Here is a sketch of what I observed:

I use a non-driven mount, so objects at high power will drift through the field of view in 30-60 seconds due to earth’s rotation. Even without the rainbow colors seen in long-exposure photos, it is a wonder to see its light with your own eyes. M57 is 2570 light years away from earth, so I am seeing the photons that left it on 557 BCE.

Conclusion

In an amateur telescope, you will not see anything that rivals images from Hubble or Webb space telescopes. However, the act of finding and viewing these objects is challenging but rewarding (and addictive). There is so much to see! I hope to get out again soon and share more observations with you.